WESTFIELD SINGING: THE FACADE OF ACCEPTANCE

Photo courtesy of Aaryan Rawal

Two “Virginia is For Lovers of Equality” signs in the office at the internship.

In the 1800s, Walt Whitman—a.k.a. “Our Great American Poet” –used his voice to celebrate our nation’s diversity. Proclaiming, “I Hear America Singing,” Whitman painted vivid pictures of this melting pot we call America. His verses capture an ideal deeply embedded in our creed: that we all have a place in the choir.

Whitman also conveyed a passionate awareness that the journey involves challenges. Our nation’s “song” is an ode to overcoming those challenges.

This column will provide a voice to Westfield students who wish to share their trials and triumphs, paying tribute to our collective spirit of resilience.

The office was, for the first time today, quiet. There were no frantic phone calls over missing canvass packets, no impatient volunteers who demanded attention, and no guest political speakers. Instead, there was a calming silence, broken only by the occasional rattle of a “Virginia Is For Lovers of Equality” poster.

“Where are you from?”

The question punctured the tranquility. Asked by a well-intentioned older volunteer, the question was not outrageously offensive, nor was it out of the ordinary. It had a simple answer, one that I readily provided: I lived in Virginia my whole life.

Unsatisfied, the volunteer asked a follow up question: “No, where are you actually from?”

Taken at face value, the interaction seems like a harmless attempt to understand my cultural heritage. Beneath their surface, however, the questions carried a patronizing assumption: my skin color was foreign. In refusing to accept Virginia as an answer, the volunteer implicitly asserted that a different nationality is inherent in a non-white skin color. This, in turn, created a narrow definition of “American” that excluded every person of color.

I wish I could say this interaction provoked some reaction from me: anger, disappointment, even offence. However, the reality is these conversations are not uncommon. Every person of color has repeatedly been asked to share “where they are actually from,” regardless of how long they have lived in the US. At this point, we are numb to the question.

What made this particular encounter memorable was where it was asked: in an office that claimed to be “accepting” and “inclusive.” Against the backdrop of walls covered with posters that celebrated our diversity, an older woman assumed that the color of my skin translated to a different nationality. The irony is palpable. However, this interaction goes beyond simply irony. Rather, it is reflective of a culture that employs virtue-signaling to obscure discrimination.

Our current approach to acceptance emphasizes performance-based actions, or actions that do not combat the root causes of discrimination, over true, substantial changes that address stark equity gaps. For example, the mere presence of a paper that said “Virginia Is For Lovers of Equality” did not prevent the woman from creating an exclusionary definition of American. If anything, it had the opposite effect. In proclaiming that the workplace was for “Lovers of Equality,” it implicitly sent the false signal that the office was accepting, suppressing sorely-needed conversations around discrimination.

In a similar vein, we constantly promote narratives such as “America is a melting pot.” Even in the headnote of this article, we claim that “diversity is deeply embedded in our creed.” On the surface, these sayings seem like harmless attempts to convey acceptance. Like posters that celebrate diversity, however, these refrains do not foster any true cultural change. Instead, they accept, without challenge, the premise that we currently embrace diversity, implying that we have already overcome discrimination. In other words, these slogans prevent us from addressing a fundamental question: are we even accepting in the first place?

These performative actions are not far-away problems; they actively present themselves at Westfield. Take, for example, our social media feeds. They are saturated with students sharing infographics on identity and current affairs. Amplifying this content is not inherently bad. It can spread valuable information and provide avenues for students to affect reform. However, a four sentence Canva graphic does not accurately summarize centuries of racism, nor does it cultivate a more accepting environment

What will generate change is recognizing the impact of our personal actions. In particular, we need to acknowledge that we can, often unknowingly, create unwelcoming environments for marginalized students. For example, FCPS’ youth survey in 2018 found that 50% of LGBQ youth experienced depressive symptoms and 34% of LGBQ students have seriously considered suicide*. With this in mind, it becomes clear that seemingly trivial behaviors that stigmatize communities, such as using gay as an insult, do have severe consequences. As such, sharing graphics on social media, without changing our behaviors to reflect acceptance, is a superficial action that does not foster inclusivity. In fact, it can directly contribute to an unwelcoming environment. The same individuals who share these posts often use them to absolve themselves of intolerant behavior, rationalizing that the amplification of a Canva graphic negates unaccepting actions.

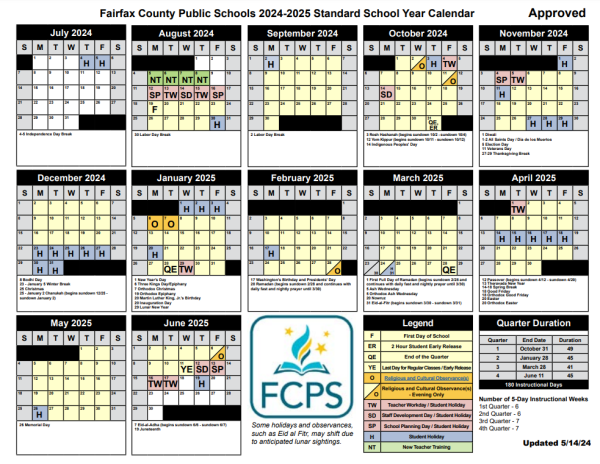

Our performative approach is not confined to students. It also impacts Westfield in a broader context. We claim that we embrace diversity, touting that we speak 80+ languages daily. Yet, marginalized students face stark achievement and punishment gaps. As ProPublica’s Miseducation project notes, white students are three times as likely to be enrolled in AP classes compared to Latino students in FCPS, and two times as likely compared to Black students. Moreover, Black and Latino students are 4.2 times and 2.4 times as likely to be suspended compared to white students, respectively. If we have effectively segregated our advanced courses and discipline structures, then do we really value diversity at Westfield? Or do we only claim to value diversity to distract ourselves from the uncomfortable reality that we are not an inclusive school?

None of this is to say that performative actions have no role in fostering inclusivity. “Virginia Is For Equality” signs and Instagram infographics can send signals of positive affirmation. However, until a person of color’s answer to the question where are you from is accepted, these symbols prevent us from having meaningful conversations around the underlying causes of discrimination.

*FCPS youth survey does not ask about transgender students. As such, we do not have data on depression and suicide rates within the transgender community in FCPS.

Chloe Gayer • Jan 13, 2021 at 3:07 pm

Absolutely beautiful writing Aaryan!!

Rosie Zhou • Dec 22, 2020 at 4:19 am

Wonderfully written, Aaryan!

Ella McCutchen • Dec 20, 2020 at 9:23 pm

I was not prepared to read such a great article today but then came this. Thank you so much Aaryan I really and truly loved this and appreciate you!! So does everyone else who resonates with this message.