SAT’S ADVERSITY SCORE MAKES POOR THE NEW RICH

Photo courtesy of professionals.collegeboard.org.

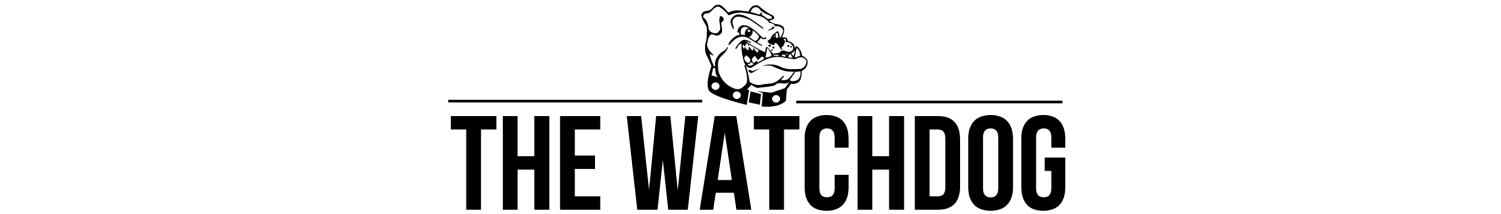

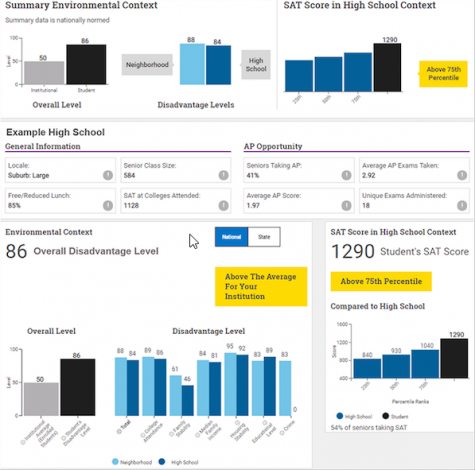

Infographic about information provided by Landscape

The College Board has decided to abandon their idea of a single adversity score, where the student’s SAT score would be combined with information on the environment in which the student lives, after disapproval by college officials and parents. The Board announced the adversity score in May, and by the end of August, the plan collapsed under the weight of criticism. However, its shadow remains in the form of Landscape, which gives students the adversity score without combining it with their SAT score. This raises the question – has the Adversity Score been canceled or simply replaced by a less extreme tool? And if so, is it any better?

The adversity score is compiled of two parts: the student’s neighborhood environment and student’s school environment, which gives everyone at Westfield the same score. Both criteria are rated on a scale from one to 100 and then averaged for a final score, where higher score equals higher adversity. The score takes into account social and economic hardships like crime and poverty.

As a result, Westfield students, a mixture of different backgrounds, will be affected differently: the rich will have their score lowered and the poor will have their score raised. The rich will benefit off the poor’s struggles, and the poor will be trampled under the privilege of the rich. If in the past Westfield was only for the affluent, now it is becoming more and more for everyone.

Similar to the single adversity score, Landscape will not account for being an ESOL student or a recent immigrant. The score does not reflect upon the students who have to move very often such as military children. The College Board is trying to account for the hardships of students from diverse backgrounds, but it is nearly impossible to recognize the hardships of completely new students or recent immigrants. Of course, students have an opportunity to point it out in their personal essays, but that does not change the fact that adversity scores will not be valid for those students.

NPR quoted College Board president, David Coleman: “I think it [Landscape] is a retreat from the notion that a single score is better. So in that sense, we’ve adopted a humbler position. That’s admitting that the College Board should keep its focus on scoring achievement. We have acknowledged that we have perhaps overstepped.”

By implementing Landscape, the College Board evolved SAT into something more than just a test. The Board’s stated reason for creating Landscape is that 25 percent of applications lack the student’s high school information, but is this information sufficient to account for the amount of adversity a student is facing?

The Stanford Daily reported that Stanford became one of the first 50 colleges piloting Landscape, without publicly declaring the change. The Daily’s interviews with high school students in the Bay Area reveal that many of them are disappointed by the College Board’s changes.

“Determining a student’s strength based on the address of their high school does not tell the whole story,” said Amber Lee, a rising senior at Mount Saint Joseph High School (MSJ), which is ranked in the top 100 high schools in the country, “Even if their schools sit in higher-income neighborhoods, students may still face other challenges, including being in foster care or learning disabilities.”

Lee finds Landscape excessive, stating that college essays would do a better job describing the student’s adversity.

Beginning next year, Landscape information on schools and neighborhoods will be shared with schools and students, but “there will be rare instances when there isn’t enough data about a high school or neighborhood to populate the tool,” admitted College Board.

This is rather surprising since the whole point of Landscape is to provide consistent high school and neighborhood information for everyone regardless of where they live. However, in reality, neighborhoods that were already well known will get a new addition to their description, meanwhile, the neighborhoods that were supposed to get more exposure will continue to stay in the dark.

The College Board has also stated that Landscape is not used to decide whether a student gets admitted or not, but instead to give more students a “fair look.” This is a rather contradictory proposition because any information a person receives affects their judgment. The fact that colleges will only have a “fair look” and not alter their judgement sounds rather unbelievable.

So, what are the actual differences between an adversity score and Landscape?

College Board explains, “[Landscape] is not an adversity score. Landscape does not measure adversity and never will. It simply helps admissions officers better understand the high schools and neighborhoods applicants come from. It does not help them understand an applicant’s individual circumstances—their personal stories, hardships, or home life. This is not the purpose of Landscape or the role of the College Board and it never will be.”

How landscape looks for college admissions officers

However, since Landscape “doesn’t help them[admissions officers] understand an applicant’s individual circumstances,” it consequently gives biased information about the applicant. The score only represents an average applicant coming from this area. That is at best fair for the middle 50% of the population. But what about people on the ends of this distribution? Because the farther one is from the mean, the more invalid the data becomes for that person. And, stating that Landscape does not measure adversity is like saying apples are not fruits. Does it not make one wonder what score would College Board officials get on their own tests?

Another key difference is that while comparing a student’s SAT or ACT score to those of students from the same high school, Landscape does not change the score itself. This is good news since now, unlike the adversity score, Landscape does not affect students’ scores directly. However, it still does not change the fact that it will impact admissions officers’ perception of students.

One of the quotes the College Board provides to prove the success of their new tool reads, “Landscape helped our application review process by challenging some of the perceptions we had of certain areas and high schools. It allows us to use tangible and consistent information as context when considering a student’s high school experience.” They do not give credit to the speaker, which already arises suspicion of its validity. The voice behind the quote says that Landscape helped them by “challenging some of the perceptions” they had. Yes, they might have changed their minds about the school, but does that not affect in what light they see the student?

Instead of creating tools to distinguish the privileged from the disadvantaged, a better idea would be to put more effort toward getting rid of these disadvantages. However, what the College Board is actually doing is encouraging those disadvantages.

Inside Higher Ed, an online publication focused on college and university topics, elaborates, “The College Board’s adversity score will give students a boost for coming from a high-crime, high-poverty school, and neighborhood. Being raised by a single parent will also be a plus factor. Such a scheme penalizes the bourgeois values that make for individual and community success… The solution to the academic achievement gap lies in cultural change, not in yet another attack on a meritocratic standard.”

Randolf Arguelles, branch director of Elite Prep San Francisco, said that the adversity score “is effectively College Board admitting that the SAT is unfair.” He added, “If the score on your standardized test requires a separate algorithm to determine if the score is actually a valid measure of ability, then perhaps it’s time to fix the test itself rather than contextualize its scores.”

Controversy regarding standardized tests is nothing new. For years, scandals have erupted after parents paid someone either to take a test for their children or to change their results. Colleges have been growing more concerned about the unfairness of the exams. More and more schools are now transitioning to test-optional.

“It’s hard not to wonder what else might be behind the College Board’s actions. The inclusion of ‘AP opportunity’ seems like an overt ploy to get more high schools to implement the AP curriculum. We know that the College Board has been losing market share to the ACT, so is this a business decision intended to reverse the declining revenue?” Top Tier Admissions, a college admissions consulting company, wrote in their blog.

Indeed, it is possible that one of the incentives the College Board had for implementing Landscape is to promote AP classes. Given that AP participation and performance is part of Landscape, students might feel like they have to take more AP classes to be considered by colleges.

Michael T. Nietzel, a former president of Missouri State University, and a Forbes writer, said that “the fact that the College Board does not want students to know their adversity scores reflects their own discomfort with the concept. And for good reason. It’s a potential source of self-handicapping and self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The College Board is not only confirming that their test favors the affluent, but also enforcing the notion that one is going to get bad scores if one is poor.

After receiving criticism on the fact that the College Board does not share the adversity scores with students and schools, the Board declared that they will start reporting the scores starting the next admissions cycle. A plausible reason for College Board to not share the adversity scores may be that once the students see them, it would become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as discussed by Nietzel. However, students have a right to know any information that is used to determine their college acceptance. College Board does not have a choice on this issue: they have been criticized to a point where people have lost faith in them. They have to be transparent in what they are doing if they want to make people trust them again.

To conclude, the College Board has been fervently trying to make up for the recent scandals regarding cheating on the SAT and secure their place on the market. Their new tool, Landscape, is a replacement for the highly criticized single adversity score. A lot of the Landscape information was already available through the state and federal government websites. But besides organizing it in one place and making it more convenient for colleges to use, the College Board converts this information into a score, therefore decreasing its validity. The fact that the College Board decided to create this tool reveals they see that their test is flawed. Regardless, Landscape is a biased metric. Many students will be unfairly given a number that says nothing about the difficulties they are going through in their neighborhood. The tool might even fail once again after a new wave of criticism that will likely arrive once students start seeing their scores.