It’s fourth period, and I’m rushing to get behind the heavy orchestra room door before my grumpy teacher closes it shut. The fluorescent, familiar lights shine down as I glide inside. An array of different violins scatter the room: the standard, the one that wants to be a violin, the bigger one, and the biggest violin. The orchestra department is one part of the Westfield musical trifecta, with three levels, different stringed instruments (violins), and a whole lot of Asians.

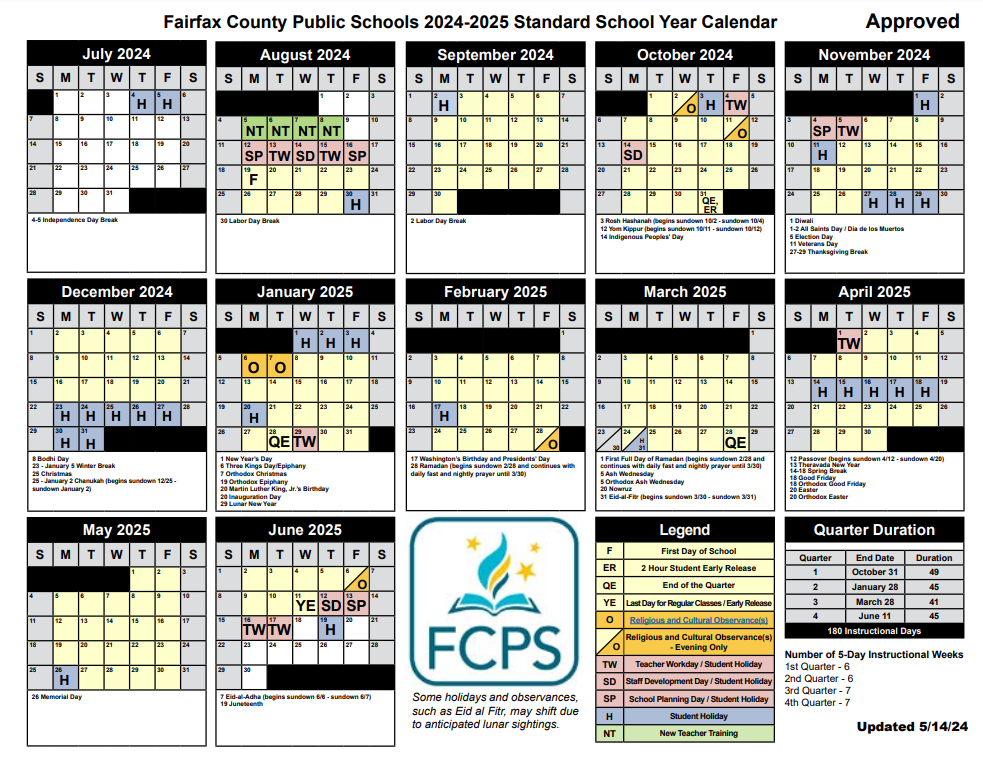

Westfield High School’s current Chamber Orchestra consists of 48 kids, approximately 52% of which are Asian students. As an orchestra student since fourth grade, every single school orchestra I’ve been a part of has been mostly Asians. I didn’t notice this overwhelming majority until middle school, where I can say without a doubt, I met–at most–three non-Asian students. In all of the violin and piano competitions I’ve entered, my opponents were all kids I knew from the local Korean church. With a single look at other FCPS high school orchestras, all I notice now is the concentration of jet black perms, tan skin, and glasses. If you read the programs, it’s hard not to notice the imbalance between Lees and Smiths.

From a young age, my Asian parents drilled the importance of knowing how to read and play music into my head. According to the New England Board of Higher Education, musical education from a young age can help develop enhanced language skills, improve memory, strengthen hand-eye coordination, encourage smarter study habits and teamwork, and accelerate mental processing/problem-solving. However, rather than aiming to follow the advice of the New England Board, I’m sure they just wanted something to brag about to other Korean families. When I talked about this with my other Asian friends in orchestra, I realized that we shared many of these experiences, including the common piano to violin pipeline.

“Every single Asian kid has been forced to play an instrument when they were younger. I think you can chalk this up to Asian parents trying to live vicariously through their children,” Westfield High School Chamber student Tahseen Azad, 12, remarks. Many Asian parents immigrated to the United States for better opportunities and education. In most cases, they wished to shape their children’s future with resources that they never had. My mom’s child pianist career was cut short because of a lack of funds, and my dad never got to try an instrument for the same reason. Both of them always voice their regret for never pursuing music further. “My mom played the harmonium but never got formal lessons. My dad has never played an instrument, but has always loved the sound of the violin. It’s funny because they set me up to do the American equivalent of the harmonium, and now I also play the violin,” Azad reflects.

Asian parents are notorious for their methods of discipline. Their creative ways of evoking fear in their children have been comedized in all corners of the internet. Interestingly, the enrollment of their kids into musical education is also a way for Asian parents to enforce their parental authority.

“The discipline to pursue music and consistently practice is valuable to Asians because it keeps children accountable for their efforts, and it’s obvious when they haven’t made any,” Sharlene Chiang, 12, states. Personally, I practiced violin pieces simply out of sheer fear of my mom’s reaction to a flat note in the middle of a recital. My stern teacher who came straight from Asia was also a source of my worry. During the peak of my musical activity, I was practicing every day for at least an hour; however, the strict regimen of violin practice carried into other parts of my life, and my productivity began to soar. “It was scary playing piano for my parents. I knew that a wrong note would show my lack of serious practice, something that they ordered me to do every day,” Chiang recounts. “But I think that this fear translated into something good when I got older. I’ve grown good habits for school and work.”

Sure, many Asian parents provide an insane amount of resources for their children to excel in music, just to violently force them to do something the parents themselves never could; but, I hope that those same kids can say that learning how to play an instrument turned out to be a blessing like it did for me. Admittedly, rather than an innate talent for music, I think that the biggest contributing factor to my “success” in high school music was accessibility to a private teacher and other extracurricular resources. Without these things, I doubt that I would have been able to enter high-level orchestras or even know how to practice on my own, and I’m eternally grateful to my parents for giving me these gifts (even if they once seemed like burdens).

Next time you see an annoyingly large majority of Asian kids in the violin section of your orchestra, instead of labeling them as overachieving, pretentious know-it-alls, I hope that you think of them as a product of their parents’ love and generosity. They are taking up all the space in those chairs because their parents care.