DISINFORMATION: AN UNSEEN PLAGUE

Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Rioters outside the White House on January 6, 2021.

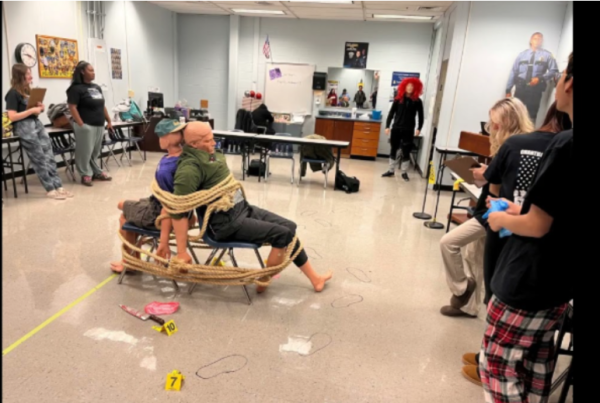

January 6, 2021, 2:00 PM; thousands of people jeer and wave flags outside the Capitol building in protest. The president’s words, speaking of election fraud and an unfair election, are repeated by the crowd as they breach the police barricade and then the doors of the building. The senators are escorted to safe locations as the mob storms the hall. Police officers who try to calm the situation are beaten and bruised. One woman from the mob is shot and killed. Eventually, the mob is forced to dissipate and leave.

In the following days, came the reports of the aftermath: five people killed, 700 people prosecuted, and 60 court cases. Every one of which speaks of the information that drove these people into a frenzy. Their actions turned out to be driven by falsehoods and lies. To put it simply, all of this was promoted by a great deal of disinformation.

Disinformation is different from misinformation; misinformation is often information believed to be true and spread without knowledge of its falsehoods. Disinformation is spread with the explicit intention of harming and deceiving others. Frequently, disinformation can be hard to spot, especially for the less informed, and easily able to influence large numbers of people into believing false narratives and committing acts of violence.

Disinformation has been used by many people in the past for fear mongering and their own gain. The reasons for such motives can range from advertising products like essential oils to active revenge. Take, for example, this famous historical event: the Witch Hunts. According to the Library of Sidney, in 1484, a monk named Heinrich Kramer had previously tried to accuse a woman by the name of Helena Scheurbin of witchcraft, as well as six other women who had not attended his sermons. When the judges did not find Helena guilty, Kramer stalked her out of hate before the judges banished him for a litany of illegal crimes. It was then he turned to disinformation.

Kramer then wrote the Malleus Maleficarum, also known as the Hammer of Witches. This book was full of all the hate he had built up over the years mixed with his beliefs of witchcraft being a crime worthy of the death penalty. Despite how many people recognized that it was going to hurt vulnerable individuals, many more still took it and absorbed it as fact. The Witch Hunts lasted 300 years and ended the lives of up to 600,000 innocent people (at conservative estimates).

For a more modern example, there’s the internet phenomenon known as QAnon. Starting on the platform of 4chan, the conspiracy theories sown by the user known only as “Q” have spread widely under the false pretense of the user being part of the government. Q’s many wild predictions and claims have driven it’s followers to make death threats against elected officials, incite several violent incidents, and sink deeper and deeper into their dystopian world view.

They accuse many celebrities and democrats of being part of a sinister and secretive Satan worshipping, cannibalistic, and child trafficking global cabal. The cause of QAnon supporters’ blind fervor is largely due to active disinformation campaigns that have also plagued the federal government. It has nonetheless led to a state of tension between the two political parties of the US, and is likely to cause more of a rift moving forward.

Disinformation can easily affect schools, as well. The easiest way for disinformation to spread in the modern world is through social media. The biggest culprits of disinformation are Facebook and Twitter. Oftentimes, those who seek to gain something from misleading people do it through social media as it can reach hundreds, if not thousands, of people in an instant and spread from there.

When Geoff Case, government teacher, was asked about how theoretically dangerous disinformation can be, he opined, “In mild circumstances, it can cause people to engage in street violence, in severe cases it can alter an election for either party who benefits from the lie, and in extreme cases it can theoretically trigger a civil war or revolution.”

When William Goldsmith, English teacher, was asked the same thing, he too noted, “I think disinformation is incredibly dangerous. We can just look at the most recent example. We’ve had a global pandemic that has spread to essentially every corner of the earth. A virus that can easily be transmitted and kill people; in the United States, alone, like 700 thousand people. I think that shows how incredibly dangerous misinformation and disinformation is when you have families torn apart because somebody read something on Facebook, or wherever on social media, and they want to believe that rather than trust the medical professionals, and start taking medications for horses because somebody said the idea was a good one.”

Goldsmith added, “In the second half of the 20th century, nuclear war was probably the biggest threat and fear that everybody had. I think that in the 21st century, the biggest threat and biggest concern that we should have is the spread of disinformation to tear societies, countries, and governments apart.”

While it can be hard to know what information out there is dishonest and hurtful, it is worth knowing that not every situation is black and white. If you are worried about being targeted with falsehoods, look at the other perspective from what is being told and come to a conclusion once both ends of the spectrum have been explored. Check to ensure that the people feeding the information are credible and if not enough information is available, run interviews and experiments to find out.